This is a feminist interpretation of a feminist interpretation of Peter Pan

The story of Peter Pan has never been my favourite. I mean with all the magic, pirates, mermaids, sassy fairies and three-dimensional characters, you’d think I’d love it. And as a practicing woman-child parts of me really do. Honestly, who can ever get enough of swashbuckling adventures, flying, massive amounts of sass and the prospect of never having to grow up? But in all the interpretations I’ve seen, none of them resonated with me.

And ironically, (as I’m reviewing a play about never wanting to grow up) now I’m older, I understand why. Peter Pan, as a classic, is problematic for contemporary reimagining’s. Whenever I’ve watched any interpretations I’ve anticipated having to grit my teeth through uncomfortable scenes. I know. J.M Barrie created Peter Pan as a character in 1902 and staged his most popular version of the play in 1904, so we are talking about a play that was constructed through the lens of The London Victorian era, you know, way before Western media truly considered the negative impact of racial and gender-based caricatures and stereotypes (although some would wonder if they do even now, here’s to looking at you Hollywood). But after enduring the Disney cooperation’s “What Makes The Red Man Red” I had long since disconnected with the Peter Pan franchise entirely. (That’s not to say I didn’t adore Robin Williams in Hook or have my first androgynous awakening from the 2003 version). But if we put the racial problems aside for a moment there’s another reason why I never connected with it.

Like the majority of adventurous tales I was told when I was growing up, the story is mostly boy-centric and Little Luci was tired of it. Wouldn’t you be if the extent of your female representation were either: Wendy, whose character development hinged on her embracing gender roles and gracefully understanding the steps towards maturity? Or Tink, who though is promising and fantastically complex, has some serious hang ups that stop her from just having some magic fairy fun? Or Mrs Darling, a somewhat forgettable character, and lastly, Tiger Lily, who though was a person of colour, her presence was minimalist and only there as a device to show how great Peter Pan was at fighting off the Pirates.

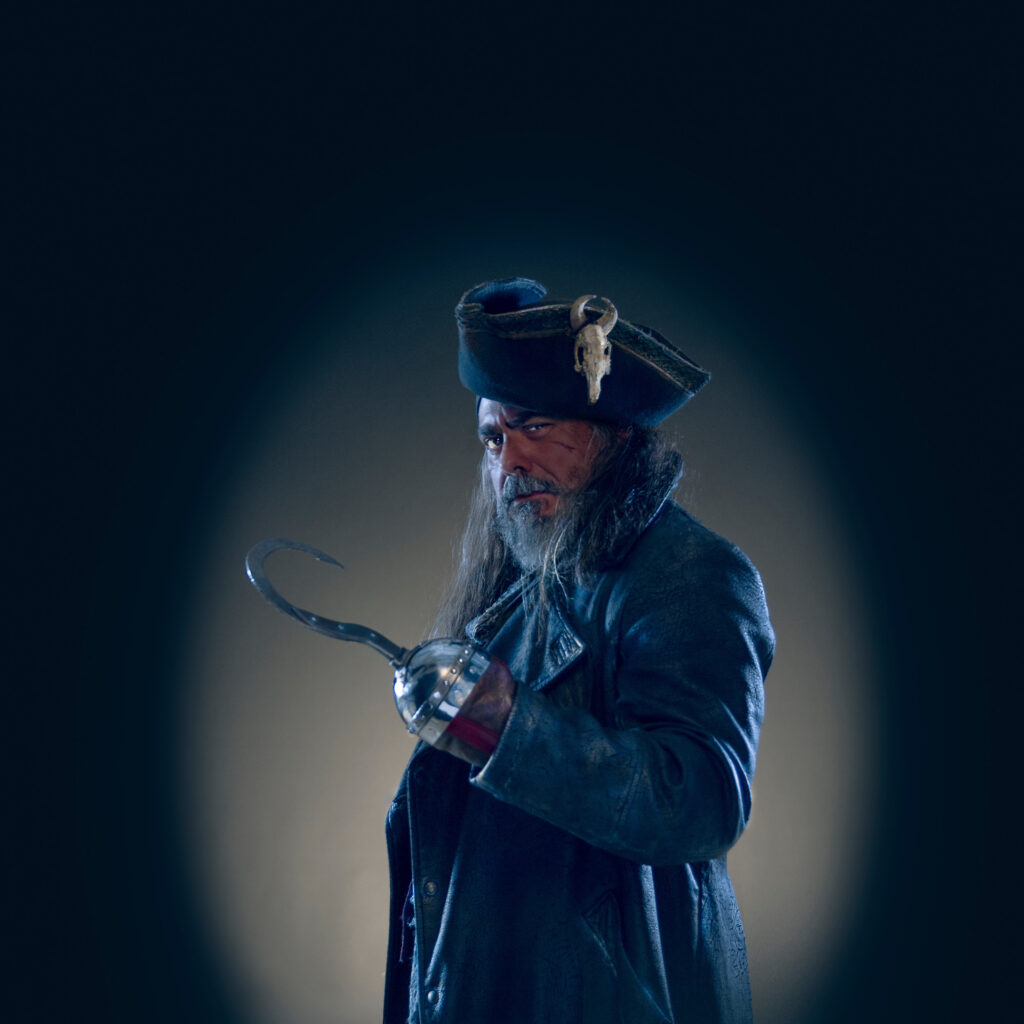

I mean I had no desire to be any of these characters. If anything I wanted to be Pan. Pan looked like he had fun. Or a Lost Boy. They looked like they had fun. Or even Captain Hook (villainy has always intrigued me). I didn’t want to grow up. I wanted to fly. I wanted to be a wild child on a perfect island forever, who wouldn’t? Like I said, the premise was there waiting for me to love it, but I couldn’t.

That was, until I saw the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC)’s interpretation. They called it Wendy and Peter Pan and it hit all the right tones with me. I mean, since we are talking about The RSC I don’t feel the need to wax lyrically about the strength of the actors, or the beautiful movement choices, or the epic grandness of the technical and staging design or the high production value. After all it is the RSC. They’ve got a reputation to uphold and I don’t want to spoil anything for you.

But what I do want to talk about is how this version helped me to understand the story of Peter Pan in a new way. It stimulated me as an adult with some chunky food for thought on its meatier themes of death and youth, while still inviting the Little Luci in me to find characters and scenes I’d wished I had the opportunity to hear originally. It was a delight to watch on the premier night with so many young people in the crowd. They cooed and awed and cried and laughed in all the right places, which is testimony to the magic of the show. It successfully transports the viewer to a magical world where everything is exciting and every scene is engaging.

It was also satisfying on another level. It shone light on the experiences of the women of the play. Not just as Peter’s love interest, or a device to show how great he was or how evil Hook was. They had real and strong developmental moments. Mrs Darling, Wendy’s mother, wasn’t just a minimal character, she did something for herself and was seen as a sympathetic but strong maternal figure who loved play as much as her children in spite of struggles.

And Wendy wasn’t in Neverland just to play an extended game of Pretend House with Peter and his Lost Boys but had her own mission, which she succeeded in. As did Tiger Lily, who, with a bit of writing genius was a person of colour that wasn’t offensive, serving as an interesting historical parallel to our own world, and was on all accounts a warrior (Little Luci wants to be her at playtime). Tink, who found her own brand of happiness and wasn’t your average ordinary interpretation of a fairy. She was rough and tumble with gentleness to her.

Like I said, all these ladies had full characters with strong back stories and complex, independent thoughts which enabled them to save themselves, and those they loved. Actually at one point the girls on Neverland; Tink, Wendy and Tiger, join together to overcome a Pirate-based problem which felt was sublime. Forget the glorification of tearing each other down, female solidarity is the story little girls need to be hearing.

There was also space for gender-role fluidity with the male characters, which was perfect. Needless to say the script was great, thanks Ella Hickson, because though the play was a feminist interpretation it wasn’t just about the ladies. The males were equally integral and well considered (and isn’t that what feminism is truly about)?

Secondly it used the elements of fantasy to tackle some pretty heavy topics. It is speculated that J.M Barrie wrote Peter Pan in tribute of his fourteen-year-old brother who died in an ice skating accident when he was quite young. That kind of solemnness and gravitas is what sews this interpretation together. It tackles very adult issues of grief, discontentment and growth with great care. It offers a space to feel and heal by using its fantastic cast of characters to instil a sense of belief and comfort.

Thirdly it nodded at the suffragette movement by adjusting the timescale of the story forward by a few decades. This was incredible to watch from a historical perspective. As the viewer we witnessed Wendy’s frustrations with Peter Pan, who decided he no longer wanted to play Father anymore while she had no choice but to be Mother despite it not being her ambition, and at the same time observed Mrs Darling’s frustrations which were also associated with the concept of wifely duties. Meanwhile this growing social unrest was creating a movement to address these exact issues (Read Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan).

That’s not to say it was all perfect. The justification for why there were only Lost Boys was too male-centric for my tastes and the play could benefit by being more sensitive to existing queer stereotypes. But apart from that it was a solid show and a fantastic night out.

Leading me to conclude that navigating intersectional feminism isn’t easy. Especially through premises that were created before sexism, racism and classism were carefully addressed through mainstream mediums. But when it is done, and done with consideration and care as with this particular play, it is so exciting and worth it. So congratulations to The RSC on being brave enough to breathe new and fresh life into a story that deserves to be told. Even if the social hierarchal structure it was originally founded on is upheaved, the themes of Neverland never grow old.

To end this blog, you can head down and see this incredible play for £5 (16-25 year olds) on 28th January 2016 – a New Year treat or a Christmas present for loved ones. If you purchase one £5 ticket you get access to 4 more. It’s all love. All you have to do is quote Beatfreeks when booking via box office *

L.

* This offer is only available to book via phone: 01789 403493