Think of all the stories you’ve been told. Now think of the potential stories you don’t know about. What explains the difference? Power lies in what we’re allowed to know.

It’s why representation in museums, galleries, and heritage sites matter. It affects what stories are told about the communities we belong to – whether at school, home, work, on TV, film, radio, online, in print, and elsewhere.

We cannot whitewash heritage considering how concerns over immigration have never left our news cycle. This is especially relevant as Brexit is on the horizon. It’s necessary for heritage to reflect the stories of the world around us. Without being made aware of the various histories within our communities, we risk ignorance, ‘fake news’, and incite hate speech.

So how can we use heritage to better connect with one another, empathise, and make positive change? We don’t settle.

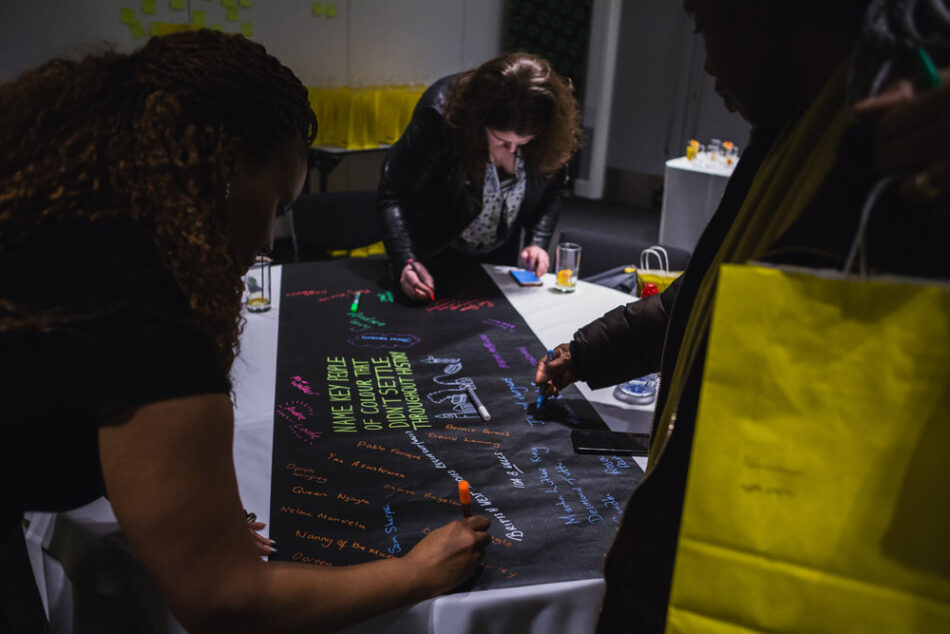

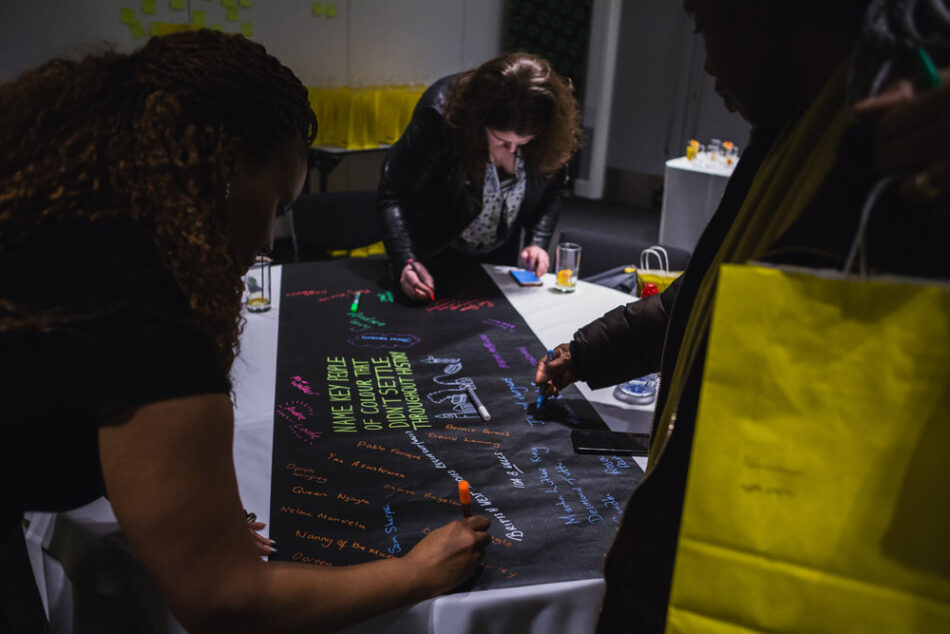

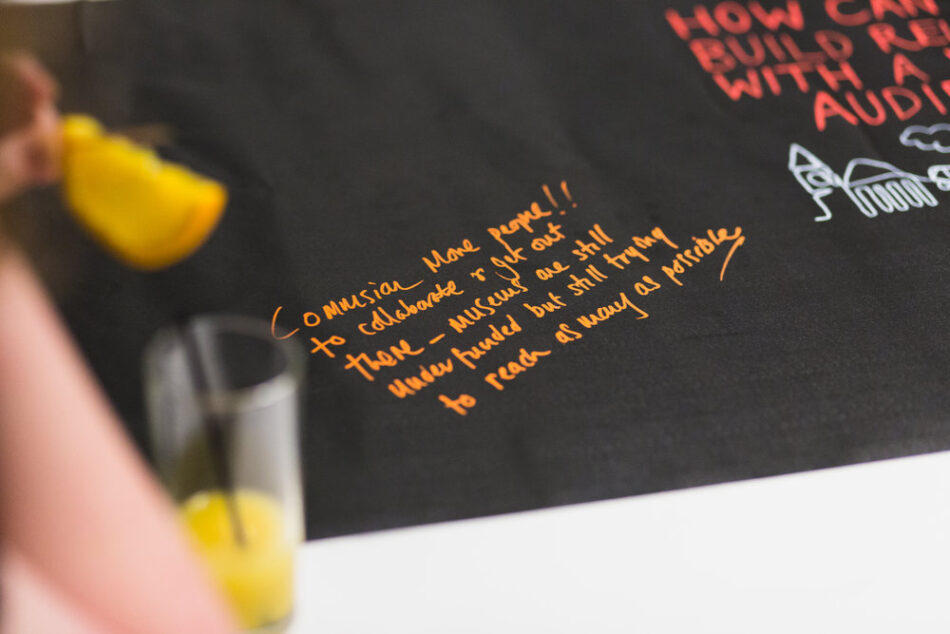

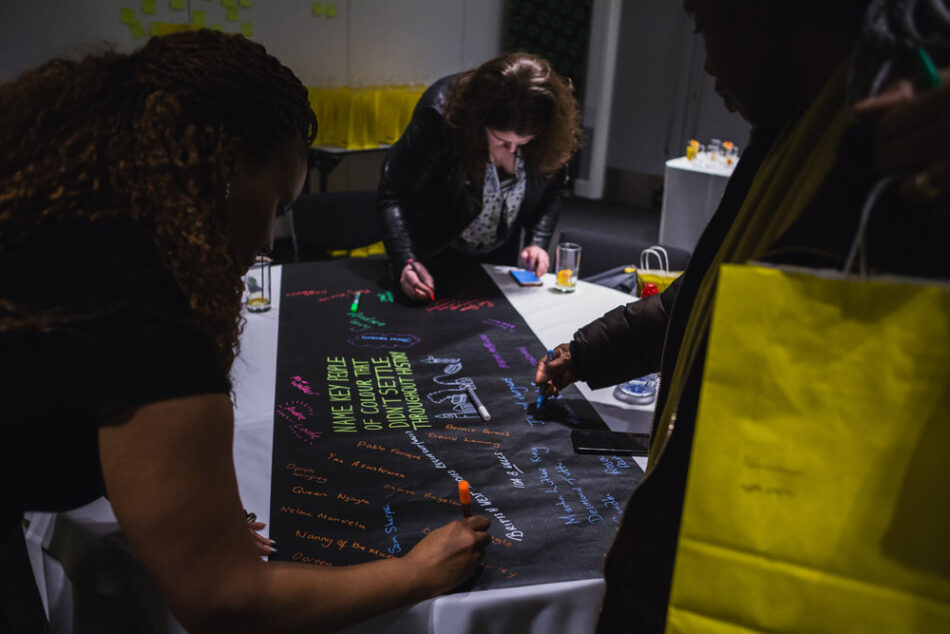

Don’t Settle, launched earlier in 2019, is the heritage project for Free Radical. To make local heritage count for our local communities, we centre young people of colour by empowering them to tell their own stories.

For our launch event, we teamed up with BLAB to talk about ‘Where’s My Past?’ It was hosted by Raza Hussain, and we had a great line-up of speakers: Dr. Kehinde Andrews, Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan, Rachael Minott, and Yasmina Silva. In getting to know Don’t Settle, our Producers also spoke about championing neglected stories.

Laura, Producer of Don’t Settle

Society uses stereotypes to define and categorise. For many marginalised people, but especially for young people of colour, these stereotypes and assumptions make it harder to access and feel welcome in certain spaces.

This is what drives Don’t Settle – to give young people of colour the opportunity to reclaim cultural heritage spaces for themselves, making them more inclusive and accessible to local communities, and ultimately more representative of the West Midlands.

Growing up in Birmingham, despite being surrounded by a diverse cultural landscape, I was never fully aware for example of the contributions of many migrant communities to Birmingham and the Black Country. I went to an inner city comprehensive, where many of my peers were from Bangladesh, Pakistan, Somalia or like myself, had a mixed heritage.

Yet our own history in this country was never something that would grace the pages of our history books at school. Nor was it something you would see on the walls of the city’s museums growing up.

In fact, it’s a history that continues to be pushed to the margins.

But why? Perhaps it’s because many of the voices that shape the stories that make up our region’s history don’t necessarily reflect the highly diverse demographic and cultures of the region that have, and will continue to shape the city.

What we should be doing is celebrating these histories. Think of the Sikhs who worked in Smethwick’s foundries, the Bangladeshis who created what we now know as the British curry or the Jamaican nurses who paved the way for the NHS.

It’s these voices and stories that we must listen to and include in our region’s history.

Sharan, Assistant Producer of Don’t Settle

Growing up, my two main streams of information were schools and museums. I loved school – but what I was taught about the history of Britain is that someone like me is new here. I learnt about the new language that I spoke, not the languages that I spoke, and I was confused as to why I knew nothing of the different cultures of my friends around me.

Colonialism. Intersectionality. Privilege. Immigration. These are all words that I was not taught and did not understand that they affected me simply because of the way education was structured both in school and museums.

Even today I feel like I am having to hunt for that information myself.

I grew up in Smethwick and Walsall but only recently did I learn that the everyday views and buildings I ignored as a child, are actually ones that connect me to my ancestors.

It shouldn’t have taken me 22 years and a personal dive into the neglected communities of Smethwick to find comfort in the fact that Indian immigration had been present since the Second World War. It was this, not my school or museums, that made me feel like I had roots and a belonging in this country.

‘The museum’ has often been seen as a place for the extraordinary … yet we identified a lack of representation and acknowledgment of the presence of our communities in museums.

Are we not extraordinary? Are our histories not extraordinary?

As Laura said, our histories as people of colour have been pushed to the margins. But for me, margin notes are not read and they are an afterthought; they are not as permanent and obvious as the ink on the rest of the page. Don’t Settle wants to bring those margin notes and print them onto the page as well. But how?

Stop settling for the margin.

Stop settling.

Don’t Settle.

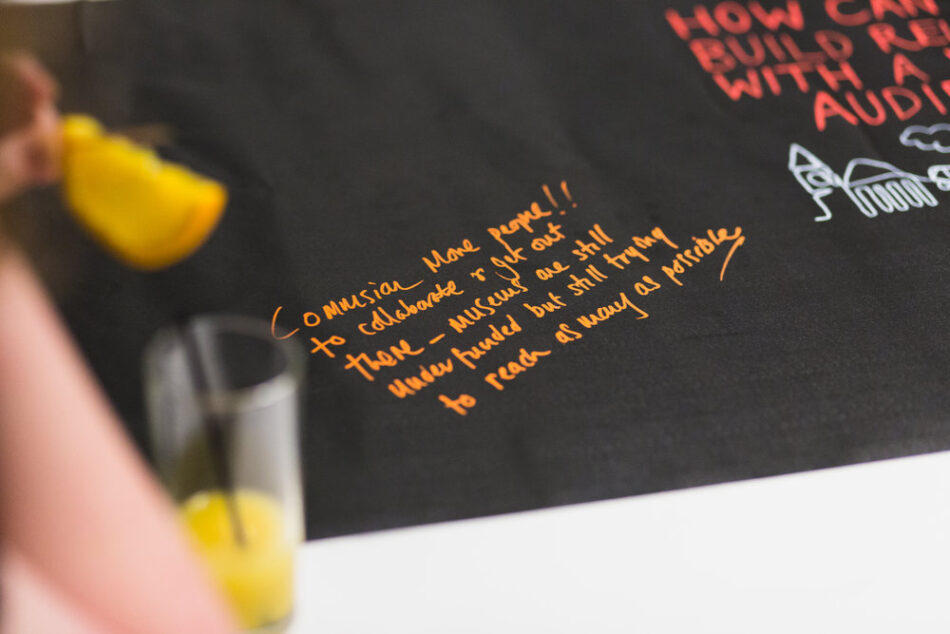

Photography by Paul Stringer